The true, original carp?

“Is this a wild carp?” That’s the question we’re asked more than any other by anglers sending us a photo of a lean-looking carp. The answer, 99.9% of the time, is: “No, it’s not a wild carp.”

Unless the angler has been fishing a river that drains into the Black, Aral or Caspian Sea, or holds a privileged position at a research institute or living gene bank, they’ve almost certainly not caught a wild carp. These fish – the original species wild carp from which all European carp were cultivated – are critically endangered to the point of near extinction; so catching one is highly unlikely.

To be clear: the correct definition of a wild carp is the true, original species carp. It’s the pure-bred ancestor of the carp that we have today. It is not simply a carp that was spawned in the wild. Those we find in the wild these days are more likely to be feral carp, descendants of once-cultivated strains. That’s okay, especially if they’ve existed in the wild for centuries. Feral is good. Indeed, it’s central to the activities of the Wild Carp Trust.

The better question to ask, therefore, when sending us a photo of a lean carp is:

- Do you think this is a feral carp?

- If so, does it look like it’s from an old strain or a young one?

- If it’s not a feral carp, is it just a young, very old, or malnourished common carp?

- Perhaps it’s a very fit-looking common carp from a river?

It’s about the strain, not just an individual fish

Just because a carp is small and thin doesn’t mean it’s from a particularly old strain of feral carp. It could be from an overstocked water, or perhaps it’s a river carp that has worked itself trim in the current. A photo, therefore, doesn’t provide all the information needed. We would require more information about the average size and shape of carp in the water. Are they all small (typically under 5lbs), lean and fully scaled? If so, this would pique our interest. Then we’d want to explore the provenance of the water. Is it old, such as a moat, stew pond, estate lake, hill lake or farm pond? If so, how old? And, ideally, does any information exist (factual or anecdotal) that indicates when the carp were stocked into the water? Hope of hopes, is there no evidence of any carp being introduced since the initial stocking?

Getting close to the ideal

The goal of the wildie enthusiast (often an angler, but he or she can equally be someone interested in natural history) is to find a strain of fish that closely resembles the original wild carp of the Danube.

All carp revert to a wild-like form through successive generations of breeding (typically in-breeding) in the wild. The greater the number of years of breeding in the wild (ideally hundreds of years) the more the fish are likely to resemble the wild form.

The original wild carp had long, lean, torpedo-shaped bodies and fins that appeared disproportionately large for their size compared to modern ‘king’ carp. This is because they had evolved to deal with the Danube’s powerful currents. As was said by one of our members, “They were a super-fit river fish, always ‘on the treadmill’, not a stillwater fish that got fat eating doughnuts on the sofa.”

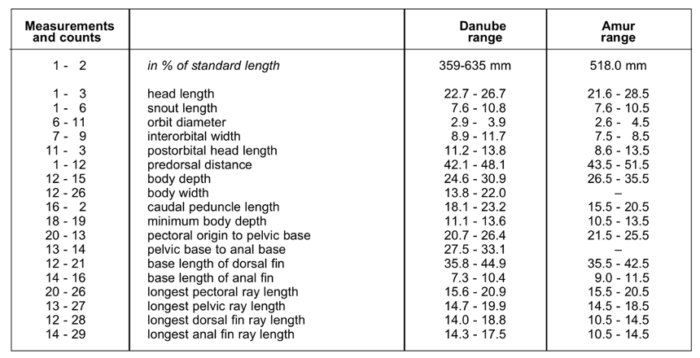

Writing about the wild carp he studied in the Danube river during the 1950s, and comparing them to studies of wild carp in the Amur River in the 1970s, Professor Eugene Balon noted their dimensions and characteristics. They were:

Whilst the table above doesn’t show weights, Prof. Balon noted elsewhere that the Danube wild carp were between 3-5kg wet mass. So, a 359mm (14in) wild carp weighed 3kg (6lb 9oz) and a 635mm (25in) wild carp weighed 5kg (11lb). That’s a higher (heavier) weight to length ratio than we see in older strains of feral carp, perhaps a reflection of the muscle mass carried by these river fish.

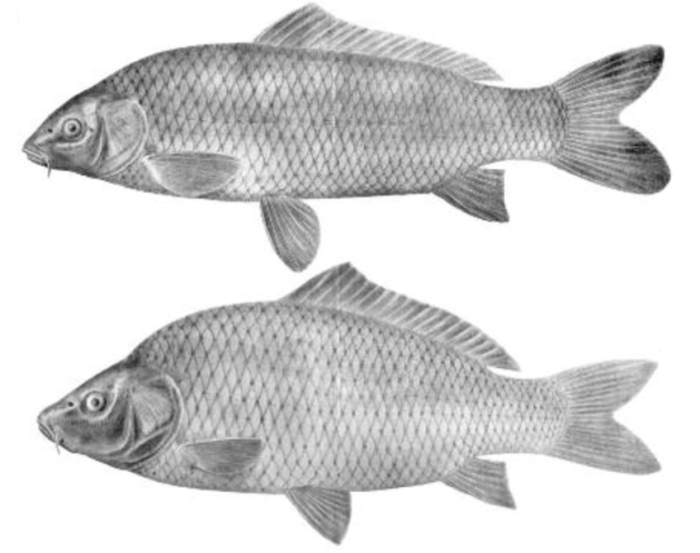

Prof. Balon also took and sourced photographs of the fish, comparing them to cultivated carp and feral carp, noting how feral carp always have a ‘notch’ behind the top of their head where it meets the shoulders. The picture below shows one such photo of wild and feral carp from the Danube.

Top fish: A true wild carp. Note the comparatively small head and large tail. Bottom fish: A feral form of domesticated carp with a characteristic notch at the neck dorsum – where the head meets the shoulders. Both fish were caught from the Danube River delta pre-1900. (Photo from Antipa, G. 1909, Fauna ichtiologic; cited in Balon, 2006.)

Professor Balon’s description of the carp was that they had “a long, round, torpedo-shaped body with the transition from head to the trunk forming an almost straight line dorsally, and not showing the depression (notch), typical for most domesticated or feral carps. Very regular, large scales covered the entire body, each scale pigmented dark at its joining edge, giving the body a mesh-like appearance. The basic coloration was a golden body, darker on the dorsum and lighter at the ventrum, head and dorsal and caudal fins greenish-brown, the ventral parts of the caudal fin, anal and pelvic fins, lips and barbels light with an orange tinge…The females have, on average, longer heads than males. The average length of the front barbels is about half that of the rear barbels. The females have a broader forehead than males.”

The 0.1% time it is a wild carp

Our Slovakian correspondent Pavol ‘Pali’ Timko is one of the last people to have caught authentic Danube wild carp. He sent us these photos of his phenomenal fish:

Wild-like, feral carp

Whilst the true wild carp has a smooth transition from head to ‘shoulders’, cultivated carp tend to have lumpy shoulders. This lump reduces with successive generations of breeding in the wild, with their offspring becoming more streamlined and wild-like. However, they always retain the tell-tale ‘notch’ at the back of the head where it joins the shoulders.

The transition from cultivated to wild-like shape and size is gradual and differs from water to water. Thus the age of the strain isn’t easy to assess from pictures alone. However, the extent of feral reversion can be observed.

Cultivated common carp, no reversion

- Notch or hump where the head meets the shoulders (the more cultivated the strain, the larger the hump)

- Deep and broad body, with a pronounced belly

- Large mouth with long barbules (sometimes over three inches long)

- Rounded, lobed tail with a thick ‘wrist’ where it meets the body

- Can grow to over 50lbs

Lean common carp, minor reversion

- Shoulders still likely to be present, although the fish will appear long

- Can grow to 20lbs

Feral carp, moderate reversion

- Small notch where head joins the shoulders

- Long, streamlined body

- Rounded, lobed tail, with a broad wrist where it meets the body

- Rarely grows to more than 10lbs

Wild-like carp, major reversion

- Minimal notch or hump where the head meets the shoulders

- Long streamlined, torpedo-shaped body, tapering towards the tail

- Often has a very blunt ‘snout’ to the face, especially in male fish

- Small mouth with relatively short barbules

- Pointed, noticeably-forked tail, fins often appear large for the size of fish.

- Older fish may have dull brassy rather than golden scales

- Rarely grows to more than 5lbs

The ideal shape of a ‘heritage’ wildie

There is an ideal shape of carp sought by wildie enthusiasts. This is one where the carp has a body length to depth ratio (excluding fins) of 4.5:1 (see the Wild Carp Trust logo for the proportions). The fish will have a really smooth shape, with minimal notch behind the head and no pronounced ‘shoulder’, and a body that tapers evenly to the wrist of the tail.

Wild carp guru Mike Winter is credited with championing this shape. He shared the photo shown here, of wildies he caught from a monastery stew pond in the 1960s, with Fennel Hudson in 2004, saying, “This is what you’re looking for!”